The 25th January is the day when we in Scotland celebrate the life and works of our national bard Robert Burns. Across the world people will be raising a glass of whisky and downing a mouthful of haggis, the “chieftain o’ the puddin’ race”, to commemorate the incredible work of Robert Burns, an ordinary, and imperfect man who became, after his death, extra-ordinary. Over 200 years since his premature death his many poems and songs have as much relevance to us today than ever.

One of his most famous poems, performed at Burns Suppers across the world is Tam O’Shanter. The tale is about an ordinary working man, whose sin was to simply spend a little too long at the local pub before making his way home on his trusty stead Meg. He is of course only too aware of the implications of what awaits him at home as his “sulky sullen dame” , Kate, waits at home whilst “gathering her brows like a gathering storm”.

Tam pays for his drunken state by coming across a debauched meeting of the devil and his witches and warlocks in Auld Alloway Kirk. Forgetting himself and shouting out “Weel done, cutty-sark”, he is chased from the Kirk and only escapes by the skin of his teeth over nearby Brig O’Doon (witches could not cross running water) although poor Meg pays as she “left behind her ain gray tail” which was pulled off by a pursuing witch.

Tam O’Shanter. Illustration by John Faed. National Galleries Scotland.

Burns main lesson from the poem was to warn of the dangers of drink as he says “Wene’er to drink you are inclined, Or Cutty-sarks run in your mind…..remember Tam O’Shanter’s mare”. Whether Tam O’Shanter learned his lesson that night and dared not to touch another drop of whisky is anyone’s guess. Or was he like most of us after a hard night, promising never to drop a touch of the stuff but quickly falling back into our old habits? Some quicker than others!!

As we celebrate Rabbie Burns, who would have known all too well that morning after feeling, it made me think about the role that alcohol had for our Scottish ancestors. We are only too aware of the image that the world has of Scotland – ginger hair, kilts and a ruddy face caused by an over indulgence in alcohol. Today we are far from being the world’s healthiest nation, and in my 20 years of researching my own family history I have found many examples of the impact, usually for the worst, that alcohol had on my ancestors. So who are your ancestral Tam O’Shanters? The following are examples of those I have found in my family tree and that of my wife Julie whose family comes from Berwickshire and the wider Scottish Borders.

My dad’s family – the Lawrie’s – were from good, proud farm labourer stock from across Aberdeenshire. By the mid to late 1800s some had branched out into the local granite industry that helped construct many buildings in Aberdeen as well as further afield in cities such as London. We can only imagine how hard life must have been for these people and there can be no doubt that downing a few drinks at the end of a day or at a rare social event, would have been a good way of escaping from the reality of your existence.

I know that my 3 x great grandfather William Bruce, a crofter from Leochel-Cushnie in the rural wilds of western Aberdeenshire, died in 1880 at 72 years of age of cirrhosis of the liver. A common cause of this disease is the over consumption of alcohol. There is no reason to suppose that my mum’s side of the family, the Smith and Lindsay families, who lived and worked in the industrial heartlands of Lanarkshire and Stirlingshire, would have had any different attitude on alcohol and its consumption.

My nomination for my ancestral Tam O’Shanter goes to my great great grandfather John Lawrie. He was born in 1858 in Cluny, Aberdeenshire and eventually found himself working in the granite industry around Kemnay. In 1877 he lost his father, also John, to a fever and found himself as the main bread winner for his mother and siblings. Whether that played a part in him falling back on the drink is unknown. His mother Barbara Lawrie, known locally as Babbie, ran a lodging house for quarry workers at the Whitestones Quarry just outside Kemnay. One can imagine that such an environment would be somewhat lacking in virtue and may not have helped John in his wilder younger days.

The British Newspaper Archives helps to give us a good indication of the kind of escapades that John and his cohorts got up to. It appears that the two hotels in nearby Kintore was the main attraction for them at that time as there are at least two occasions where John, probably the better for drink, falls foul of the law whilst on foot back to Kemnay.

The most notable incident was May 1876 and the Press and Journal reported on the appearance at a Sheriff and Jury Court of a “John Laurie, quarry worker…Whitestones” who, with a friend, was charged with assaulting a police officer and obstructing him in the execution of his duty!!! Whilst not explicit the article infers that the cause was drink as both were described as otherwise of “respectable character”. The fact myself, my dad and a few of my cousins served as police officers makes this story more than a little ironic.

John continued in his wild ways and on the 16 May 1879 the Evening Express reports that a “John Lawrie, quarry worker, Whitestones, Kemnay” and two friends were charged with assaulting and tripping up three “bicyclists” on the road near Port Elphinstone near Kintore when one of them demanded a lift.

John seems to have recovered from his wild ways and in due course became a well respected stone mason as well as a prize winning ploughman as shown in the picture below. His later appearances in the Press & Journal was limited to announcing him winning a prize in the well attended Ploughing matches across the area. Whether, in terms of the dangers of the demon drink, he had a eureka moment in the same dramatic manner as Tam O’Shanter we will never know.

John Lawrie. Date Unknown.

John Lawrie was something of an amateur when compared to my wife Julie’s ancestral Tam O’Shanter. He was her 3 x great grandfather Robert Clark, a blacksmith from Hume in Berwickshire. We recently found him after discovering an unusual Marriage Notice for her grandparents posted in the local Berwickshire News. Her grandmother, Janet Turnbull, known locally as Jenny, was described at the time of her marriage in the 1940s as being the “great grand-daughter of Robert Clark, blacksmith, Hume”.

Mentioning someone who had been dead for so many years appeared to be unusual and we found that the Robert Clark referred to, who died in 1877, was well respected in the Berwickshire farming community and well known for his veterinary skills, all learned and practiced as an amateur. A warm tribute appeared in the local newspaper at the time of his death.

His son, also Robert Clark, on the other hand was well known for other skills, usually gained from consuming too much liquid refreshment. Again the British Newspaper Archives describes a litany of this Robert’s escapades. In July 1870 his name featured in the Berwickshire News having been charged with assaulting a William Tait. A few months later he is arrested and appears at court from Duns Jail, charged with “furious driving on the streets of Greenlaw”, although this charge was not proven in court.

The bold Robert’s antics continued over the coming years. In August 1875 he is charged with assaulting Thomas Turnbull, the toll collector at Mertoun Bridge by kicking him and “striking him with the handle of a whip”. This is followed with an escapade on a train in St Boswells where he is charged with a breach of the peace on a train by disturbing other passengers.

His behaviour does not improve and all his offences indicate that they are committed when under the influence of alcohol. I have no doubt that Robert would have been well known by the local police and would have attracted suitable attention when “under the influence”.

In July 1884 he assaulted a husband and wife in a house in Scott Street, Galashiels with the husband’s injuries being “to the effusion of blood”. A year later, while under the influence of alcohol he takes a header over a railing in a house in Scott Street, Galashiels suffering a serious head injury and vomiting blood. In the truest tradition of the indestructible drunk, known to many a police officer, he appears to recover from these injuries. Perhaps it is my suspicious mind but given the previous incident in a house in Scott Street the question is did he fall or was he pushed?

In reality it was only a matter of time for Robert, who perhaps unlike John Lawrie, never seems to learn the lesson of Tam O’Shanter. Despite his earlier escapades in Galashiels on the 13 May 1890 he suffers an immediate fatal injury when he suffered a fall in a house at 4 Buckholmside, Galashiels, the cause of death being given as a fractured skull. He was only 58 years of age.

The impact which alcohol had on our ancestors will be seen, sometimes hidden, in most family histories, certainly in most Scottish family history. Sadly we as a society have still not learned our lesson from Tam O’Shanter. I, like most people, enjoy a drink occasionally and am particularly partial to the wonderful gins that are being made across Scotland at the moment. But in my 30 years in the police our misuse of alcohol has not changed and if anything people tend to get even more drunk today than they did before, often leading to tragic consequences. It remains tragic that alcohol continues to have such a terrible impact on people’s lives in Scotland and across the world. We may hear the story of Tam O’Shanter but as a society we have yet to take it fully on board.

However it does tell us that the lessons from Robert Burns’ wonderful songs and poems are still relevant in our society. As well as Tam O’Shanter amongst my favourites is A Man’s a Man For A’ That. The line “the rank is but a guinea’s stamp” is wonderful and its meaning resonates so much in this day and age where people of privilege and riches often fail to appreciate their role and responsibility to those less well off and/or lucky than they are.

I wish you all a healthy Burns Night.

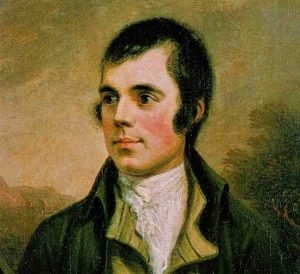

Robert Burns (1759-1796)

Sources: Various. British Newspaper Archives: www.britishnewspaperarchives.co.uk

Recent Comments